Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Welcome to Arts Radar, a monthly column breaking down key developments in contemporary art and the wider worlds of design, music, cinema and television.

It’s not an easy moment for the art market. New York’s ADAA fair was just cancelled. Giacommetti and Warhol went sideways at auction. And as the art world gears up for the summer holidays, its group chats are filled with speculation about which galleries might shutter next. “How did we get here?” insiders are asking themselves. “And how do we get out?”

It’s time to talk about a key culprit: the art-market’s financialisation over the last 25 years.

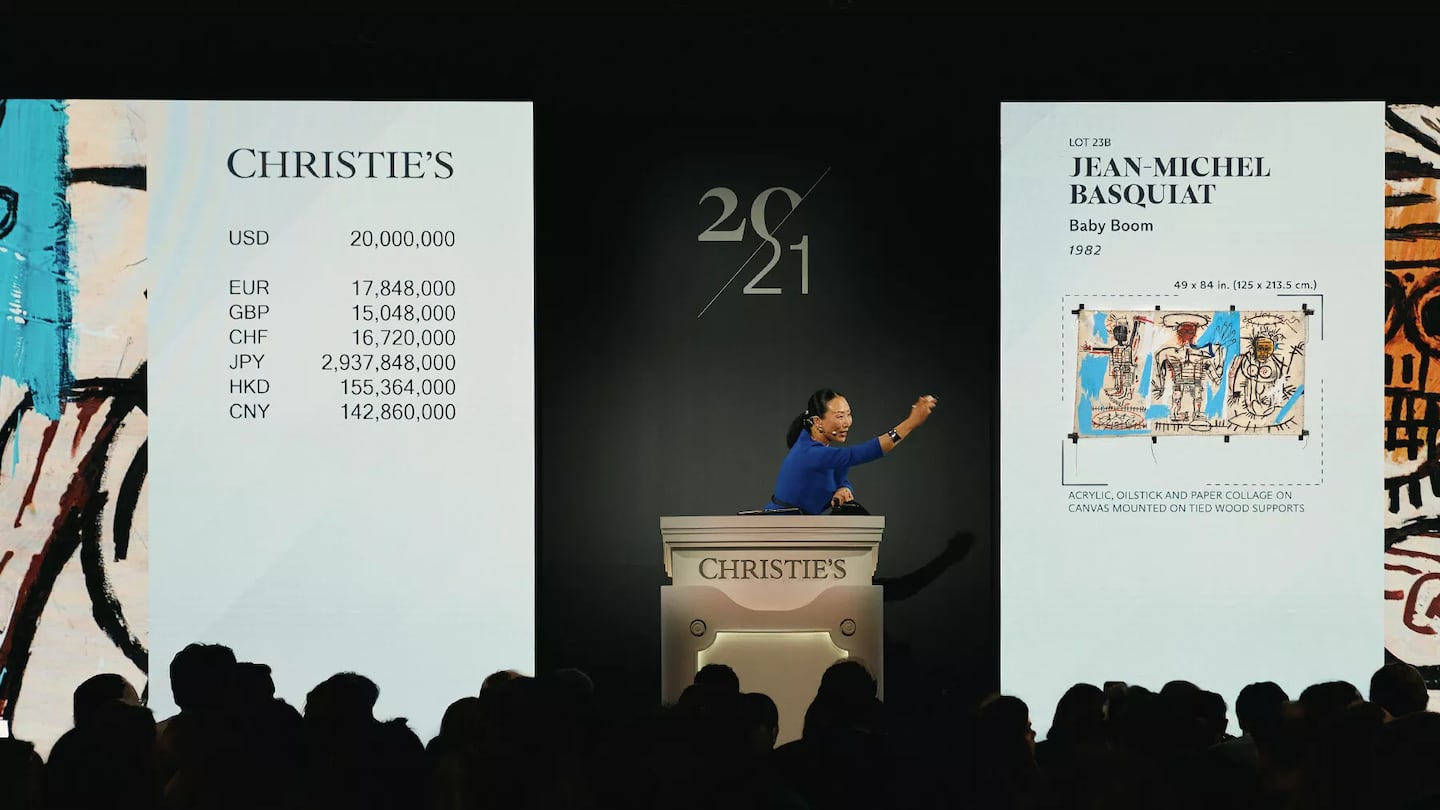

At the time, it seemed a small thing: Phillipe Segalot, who ran the Post-War and Contemporary department at Christie’s in the late nineties, decided to ignore the conventional wisdom that art works less than a decade old weren’t “auction-ready.” Record results proved him right. By the mid-naughts, it became common to see works that were two or three years old on the auction block. In the art trade this is condemned as “flipping” and hated by artists and galleries alike. But others, especially outsiders, saw the big returns being generated by “fresh paint” artworks — to them, the art market looked not only rich with opportunity but also blessedly free of government regulation.

ADVERTISEMENT

Thus a new paradigm entered the art market in the early 2000s, framing art works not as symbolic goods whose value was rooted in cultural significance, but rather as financial assets akin to stocks and bonds, where what mattered most was the return they might yield.

To be clear, going back to the emergence of commercial galleries during the Enlightenment, there were always people who bought art with the intention of reselling it at a profit. But financialisation led to the introduction of new products and practices in the art market.

Among the most visible was the proliferation of new “art investment funds,” operating like hedge funds in that they gathered money from individual and institutional investors and deployed it to build a portfolio of pieces, destined to be liquidated at a profit within a specific time horizon. The most prominent was the Fine Art Fund Group, launched in England in 2004 by Phillip Hoffman, who had spent 12 years on the finance side at Christie’s.

“Originally we didn’t plan to be focused on contemporary work, but the big returns were there,” recalls Morgan Long, who worked in senior roles with the group for 20 years before going independent in 2023 as an art advisor. “We were buying artists like Peter Doig and Christopher Wool when their prices started jumping. There wasn’t any real research backing our strategy, but we had a magic team when it came to hearing the whispers of the market.”

As the notion of art works as an “alternative asset class” gained credibility, dealers started encountering a new genre of clients. “In the 2000s, we suddenly had people coming to us wanting to build ‘portfolios,’” recalls renowned Berlin gallerist Esther Schipper, who also has spaces in Seoul and Paris. “Then they would call six months later and complain that the prices of the works they bought were not rising.”

Then came fractionalisation, whereby investors bought a very small portion of an art work poised for profitable resale. Masterworks, where shares in artists such as Picasso, Kaws, Bridget Riley and Barkley Hendricks are currently trading for a few hundred dollars, has always openly considered its client base to be far bigger than just ‘art people’ — its website proclaims “985,127 users are building a better portfolio with us.”

Loath to miss out on the action, traditional banks like UBS and Citi expanded their wealth-management offerings into art advisory services. And while such banks rarely loaned money against collections, a new category of “art lending” companies emerged. The most prominent was Athena Art Finance, founded in 2015 by Olivier Sarkozy, backed by private equity giant Carlyle and requiring a $1 million minimum valuation per work to get a loan.

At the lower end of the lending spectrum was Levart, whose website read like an ad for an American payday-loan outfit: “5,000-$1,000,000+. 4 percent monthly. No fees. No minimum turn. Money tomorrow.” It was launched by ArtRank founder Carlos Rivera, who was described as “a sort of Jim Cramer for the fine arts” in a 2015 New York Times piece entitled “Art for Money’s Sake,” which went on to explain: “ArtRank uses an algorithm to place emerging artists into buckets including ‘buy now,’ ‘sell now’ and ‘liquidate.’” Predictably, artists were outraged.

ADVERTISEMENT

“There was a step change in how people spoke about art in public,” remembers veteran art-market analyst Tim Schneider, who writes the Gray Market Substack (and also contributes to The Business of Fashion). “Younger collectors started one-upping more established ones who, behind closed doors, were using the same profit-minded terms you heard on Wall Street.”

Artworld financialisers often cited the research of Jianping Mei and Michael Moses, who, starting in 2000, studied the repeat sales of 10,000-plus single artworks at auction and concluded that the art market had outperformed the stock market.

Auction houses also started pushing a financial device known as the “third-party guarantee,” externalising their risk in cases where they had promised to buy an artwork if bidding stalled below an agreed minimum price. Not wanting to get stuck with too many freshly “burned” pieces, the houses turned to wealthy outsiders as a safety net. In exchange for taking a large portion of the auction house’s upside if bidding went higher, those third party guarantors contracted to buy the unsold piece. Basically, it’s art-market reinsurance.

So, how did the financialisation of the art market work out? Pretty poorly. Especially when you consider the knock-on effects.

For a start, it failed to create significant new revenue models — its entire raison d’etre — and many art-investment initiatives failed, disappeared or pivoted.

The Fine Art Fund did five funds before rebranding in 2016 as an advisory service, the Fine Art Group, working with individual collections. “It became harder to get investors into a fund structure,” explains Long. “There started to be too much expensive administration, especially by the time we were running the third-party guarantee funds. We set records with some of our guarantees, but we also ended up owning things that didn’t sell at auction, and then we had to go find buyers in the private market.”

The last ArtRank Public Index was posted in 2017. When people studied the Mei Moses methodology more closely, they realised it does not factor in pieces that are never resold — a major flaw in analysing an industry that rapidly surfaces new market darlings, many of whom also rapidly exit stage left. In 2019, having taken $280 million in investment, Athena Art Finance was sold for $170 million to a fintech platform.

Just a few months back, The Financial Times published a piece titled, ”Art Lenders Issue Margin Calls as Painting Prices Fall,” revealing that collectors were being asked to add additional works as collateral for existing loans.

ADVERTISEMENT

“The math doesn’t hold for art as investment,” says Hong Kong-based collector Shane Akeroyd, who has decades of professional experience in finance. “If you look at stocks or bonds or real estate, for example, they all possess liquidity. It’s rare that you have a ‘jump to default,’ where prices collapse to zero overnight. That only happens in extreme cases like Enron. In art, it happens more commonly. Even when the market for an artist seems to soften, you sometimes can’t sell it. And the valuation is subjective — you don’t have balance sheets or economic data you can examine. There are much surer and easier ways to invest your money.”

Given that volatility, investing in art effectively would require enormous capital, Akeroyd and Long agree. You would need to purchase multiple works by dozens of artists, using a Silicon Valley venture capitalist’s playbook, whereby a single “unicorn” counterbalances dozens of failed bets. And in a market where the prices for younger artists jumped over the last decade, those dozens of positions cost more to build than ever before, making it that much harder for a portfolio to yield profits

What’s more, the financialisation of art positioned the sector in dangerous terrain, compromising its strengths while highlighting its weaknesses.

Yes, it definitely brought a lot of new investors into the field. But as significant returns failed to rapidly materialise, few of them became actual patrons. And in countries as dissimilar as Brazil and Korea we’ve seen a cycle of markets overheating as people invest in art — and then cratering once they realise it’s not as easy as they thought.

After you adjust for inflation, the estimated size of the global art market today ($57.5 billion) is even lower than it was in 2009 in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. Worse yet, many potential patrons developed badly torqued notions about art. “Investment became the number one concern for collectors,” says Long. “When actually it belongs 5 or 6 spots down the list.”

The sales tactics at certain galleries are not helping matters. “I hear colleagues telling clients, ‘If you buy this work, I’ll buy it back from you later at double the price,’ implying that the artist’s market will inevitably rise,” says Schipper. “I don’t know if that’s taken as a guarantee, or just as a desperate sales pitch. I think it’s better to talk about owning art as a journey that you buy into. But then you get those people who find $50,000 is a lot for a painting, and in the next breath tell you about their $250,000 family safari.”

So where does that leave us? For many in the trade, reversing the paradigm shift that repositioned art from symbolic good to financial product seems like Mission Impossible: the asset-class narrative has become too pervasive to ignore.

On the other hand, the massive generational wealth shift that many see as a threat to the art world — in part because so many millennials consider expensive objects to be a burden — could instead prove a boon. After all, wealthy millennials are no strangers to luxury experiences which offer no chance of financial return, from $5,000 backstage passes to $25,000 Austrian wellness weeks.

None of these outlays are justifiable as an investment, which is why economists refer to such spends as having “hedonic pricing,” meaning that their value is based on the buyer’s derived pleasure. The fact that these buys come with social clout online only increases their value.

Here’s my proposal: The art trade needs to rapidly pivot away from selling art as an asset and towards selling art and its collecting as an Instagramable, sapiosexy pleasure for the wealthy, high IQ set, who get excited about culture, complex ideas, access to artists and the possibility of signalling all of that.

“The job of museums and galleries is to present artists in the best light, so people want to engage with their narratives,” says Akeroyd, “It needs to be cerebral, hopeful, spiritual — and definitely not transactional.”

Wishful thinking? Maybe, but after a quarter century of financialisation and the ravages it’s brought to the art market, it’s time to shift the conversation.

South Park Goes Rogue

Given “South Park” creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone’s long history of inflammatory humour, Paramount must have expected the occasional controversy when they inked a $1.5 billion renewal deal to broadcast 50 episodes of the animated series and the exclusive right to stream the previous 26 seasons. What Paramount almost certainly did not anticipate was that the duo would launch with an episode that slyly lambasted the company for both cancelling the Stephen Colbert show and its $16 million payout to Donald Trump after he sued CBS for their “election interference” edit of last year’s “60 Minutes” interview with Kamala Harris. The episode also featured Satan jealously badgering Trump in bed about the Epstein files, and an AI-generated public service announcement, in which the president stripped bare in the desert, revealing a diminutive, googly-eyed, and talkative penis. Calling the show “fourth-rate,” the White House declared, “This show hasn’t been relevant for over 20 years and is hanging on by a thread with uninspired ideas in a desperate attempt for attention.” Hanging in the balance was FCC approval for Paramount’s planned merger with Skydance Media, which was ultimately green-lit by the US regulator last Friday.

Thai Artworld Unboxing

Thailand has been a bright spot for luxury consumption in recent years. But the country’s art scene has long lagged behind Japan, China, India and most recently South Korea. In the last few years, that’s started to change: a flurry of new projects has piqued the artworld’s interests and populated our travel schedules, most notably the patron Marisa Chearavanont’s Khao Yai Art Forest several hours outside of Bangkok, which opened in February, featuring artists such from Fujiko Nakaya to Elmgreen and Dragset. Last year, Chearavanont opened her Bangkok Kunsthalle project, led by Italian curator Stefano Rabolli Pansera. And this winter will mark the final edition of Ghost 2658, the performance series spearheaded by Hong Kong-born curator Christina Li, Thai artist Korakrit Arunanondchai and Thai curator Pongsakorn Yananissorn, alongside the Bangkok Art Biennale and the opening of Dib Bangkok, designed by Thai starchitect Kulapat Yantrasast to extend the legacy of beloved maverick Thai collector Pech Osathanugrah, who died in 2023. “The Bangkok art scene is like a cross between a disco ball and an onion,” explains Kulapat. “On the surface it’s all fun and shiny, but when you scratch the surface, it’s meaningful layered and delivers spicy kicks.”

What Else I’m Reading:

Gwyneth Paltrow Becomes ‘Temporary Spokesperson’ for Astronomer Amid Coldplay Kiss-Cam Scandal [Hollywood Reporter]

AI Music Creator imoliver Signs Record Deal With Hallwood [Billboard]

Having led Art Basel from 2007 to 2022, Marc Spiegler now works on a portfolio of cultural-strategy projects. He is President of the Board of Directors of Superblue, works with the Luma Foundation, and serves on the boards of the ArtTech and Art Explora foundations. In addition to consulting for companies such as Prada Group, KEF Audio and Sanlorenzo, Spiegler has long been a Visiting Professor in cultural management at Università Bocconi in Milan and launched the Art Market Minds Academy, which just announced its Cultural Catalyst Project.